Ever since Johannes Gutenberg invented mechanically movable type that ushered in the printing process in the 15th century, the question of the survival of the book has been raised every time there has been a new technological advance.

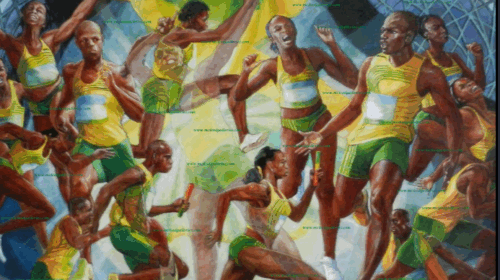

The launch of Barrington Watson’s book “BARRINGTON: 50 years of drawing”, published by Ian Randle.

Why, we should ask ourselves, is there this perennial fear that does not seem to apply to any other medium of information and entertainment? And why, after 500 years are we so afraid to accommodate even the thought of having the book as we know it, replaced by some other method of accessing information?

The fact that the question of the survival of the book is posed so often (and not just by those of us whose livelihood depends on the industry) is an indication of how connected we are as a society to this mode of entertainment and learning, that the mere suggestion of a possible threat seems to drive fear into our hearts.

But with each apparent threat, the printed book has emerged stronger with the result that today more, not fewer books are being produced, and while the sale of individual titles might have declined, the number of new titles being produced has actually grown and continues to grow.

So what accounts for the remarkable resilience of the book? Firstly, I believe that the book more than any other medium is the quintessential symbol of our civilization. It not only defines us as human beings, it is an essential part of our being. It symbolises what is orderly and civilised in our lives to the extent that even in the language of everyday life, the book assumes a central place; so for example we bring errant people ‘to book’; or we ‘book’ someone for breaking the law; we ‘book’ flights, hotel rooms and concert tickets and we ‘book’ debit and credit transactions as in bookkeeping for our businesses.

Even the most modern technologies cannot escape the overpowering influence of the book; so today we have the computer ‘notebook’; we develop vast social networks on ‘Facebook’ and we ‘bookmark’ our favourite sites on the Internet.

The second explanation for the resilience of the book is that unlike other forms of entertainment and education/information, it is (to use the metaphor of computers) both the hardware and the software. Consider if you will the music genre; once the old vinyl record became obsolete, so did the record player and the juke box. The cassette player had a relatively short life after cassettes were superceded by CDs and today, the DVD and the accompanying DVD player are fast becoming old technology, especially for the young who prefer to download music from the Internet to ipods, computers and mobile phones.

Several deaths

The music has not died but the method(s) by which we access it has died several deaths. Movie films have suffered a similar though less dramatic fate; movie cassettes and players were as short-lived as their musical counterparts, and even though DVDs have survived a bit longer, more and more people today download movies from the Internet to be watched on their computers and cell phones while in places like the US, videostore giants like Blockbuster are fast disappearing.

You can now order movies online from suppliers like NETFLIX for immediate delivery on to your TV screen at home. True, you can order the latest best-seller novel for immediate delivery on your Amazon Kindle hand-held reader but the Amazon service of the same printed book remains strong, as do the bookstore outlets around the globe selling far greater numbers of the printed book.

Instead of focusing on the perceived threats of the new technologies to the future survival of the printed book, we should be more positive and point to the many ways in which those same technologies have worked to enhance and promote the survival of the book. We need only to look at the phenomenon of digital or print-on-demand, which now allows us to print as few as a single copy of a book, or as many copies as there is the demand. What does this mean?

It means that in contrast to the old offset method of printing where you had to produce a minimum number of copies to make a book project economically viable, with digital printing you can achieve economic viability with no loss of quality on small numbers with the result that books that in the past would never have seen the light of day can now be produced and made available, even if the market is finite.

It also means that publishers no longer have to make large financial investments in printing and holding large inventories of a particular book, thus freeing up money to produce a wider range of books. Third, and perhaps most significantly, the new technologies not only prevent slow selling books from dying premature deaths – they also bring back books from the dead. The concept of an ‘out of print book’ is in fact no longer relevant.

At the same time old, rare books can now be scanned, stored electronically and printed on demand. The best example of real-time-on-demand printing is the so-called Book Espresso machine which Time Magazine described as one of the best inventions of 2009. Like the coffee-making machine after which it is named, this invention – no larger than a 6-ft high bookshelf can produce a book of virtually any size and length in 4-7 minutes from millions of titles stored in a central database, and bound and finished in a form that would be impossible for you to differentiate from a traditionally printed book. That machine is today installed and operational in over 100 locations across the US, Canada, Australia and the UK.

Matches the speed

What this machine in fact does is to match the speed of the electronic book, of say the Amazon Kindle, in getting the book to the reader in real time at no additional cost for shipping, thereby using the technology to ensure the continued viability of the printed book vis a vis its electronic counterpart.

At the end of the day, it requires of us in the business and publishers in particular, not to hold on to some bibliophilic nostalgia about how a book smells or feels, or to wax warm about the comfort of curling up in bed or on a sofa with a good book, although there is a lot to be said in defense of that luxury. Nor should we wring our hands in a gesture of helplessness and resignation in prematurely bemoaning the death of the printed book.

Rather, it behoves us to face the reality of the inexorable advance of technology and to redefine our concept of the book, to incorporate the increasing variety of modes and formats in which the modern reader or researcher has available to him or her to access information, and for us to see the book (yes, grudgingly) as simply one of a variety of those formats. In this way we will be doing a lot to ensure the continued survival of the book as we know and love it.

Contributor Ian Randle is a publisher and may be contacted at Ian@ianrandlepublishers.com

Author Profile

- ... refers to representatives of entities such as embassies, entertainment industry, creative force whose submitted work gets published on this site. Views expressed here may not necessarily represent those of the owner of this site, but are being published in the interest of the wider public. Link me here

Latest entries

AdvertorialFebruary 1, 2026Daily reads on www.antheamcgibbon.com as @ 1 February 2026

AdvertorialFebruary 1, 2026Daily reads on www.antheamcgibbon.com as @ 1 February 2026 AdvertorialJanuary 21, 2026Documents assistance

AdvertorialJanuary 21, 2026Documents assistance AdvertorialJanuary 1, 2026Daily reads on www.antheamcgibbon.com as @ 1 January 2026

AdvertorialJanuary 1, 2026Daily reads on www.antheamcgibbon.com as @ 1 January 2026 Raw and DirectDecember 21, 2025Use that rare energy in you

Raw and DirectDecember 21, 2025Use that rare energy in you